2024 has been a tough calendar year for Cymru’s men so far, there’s no doubt about that. Eight straight test match losses, a Six Nations wooden spoon and generally quite uninspiring performances have led to a gloom settling around the team.

There have been positives to cling to, specifically around the performances of young talents who have stepped up into the test arena, but as with any sort of major evolution there is unlikely to be immediate success. Things take time to bed-in, especially in elite international sport.

However, that doesn’t let the team and coaches off entirely from disappointing overall showings, and from a personal point-of-view I look particularly to the coaches here in terms of developing game plans and sending the players out to play an exciting brand of rugby that they want to be playing and that suits their skillsets.

Instead what we end up with is Nick Tompkins telling the BBC Rugby Union Weekly Podcast prior to the summer tour that Cymru will revert to a very basic and “boring” style of rugby, presumably in an attempt to strip everything away and start the attack from scratch.

That particularly manifests itself in transition, an area of Cymru’s game which has long frustrated me, as the men-in-red effectively shirked counter attacking despite having some of the best counter attacking talents around on paper in the squad.

When Liam Williams receives the kick just inside his own 10-metre line, an ideal spot to launch a counter attack from, there doesn’t seem to be any question in his mind about the fact that he’s going to put the ball up in the air to chase.

That ambition to play a bit is an element of why Cymru fail to counter attack effectively, but there’s also the simple problem that there is clearly little, if any, work done on counter attacking shape in training.

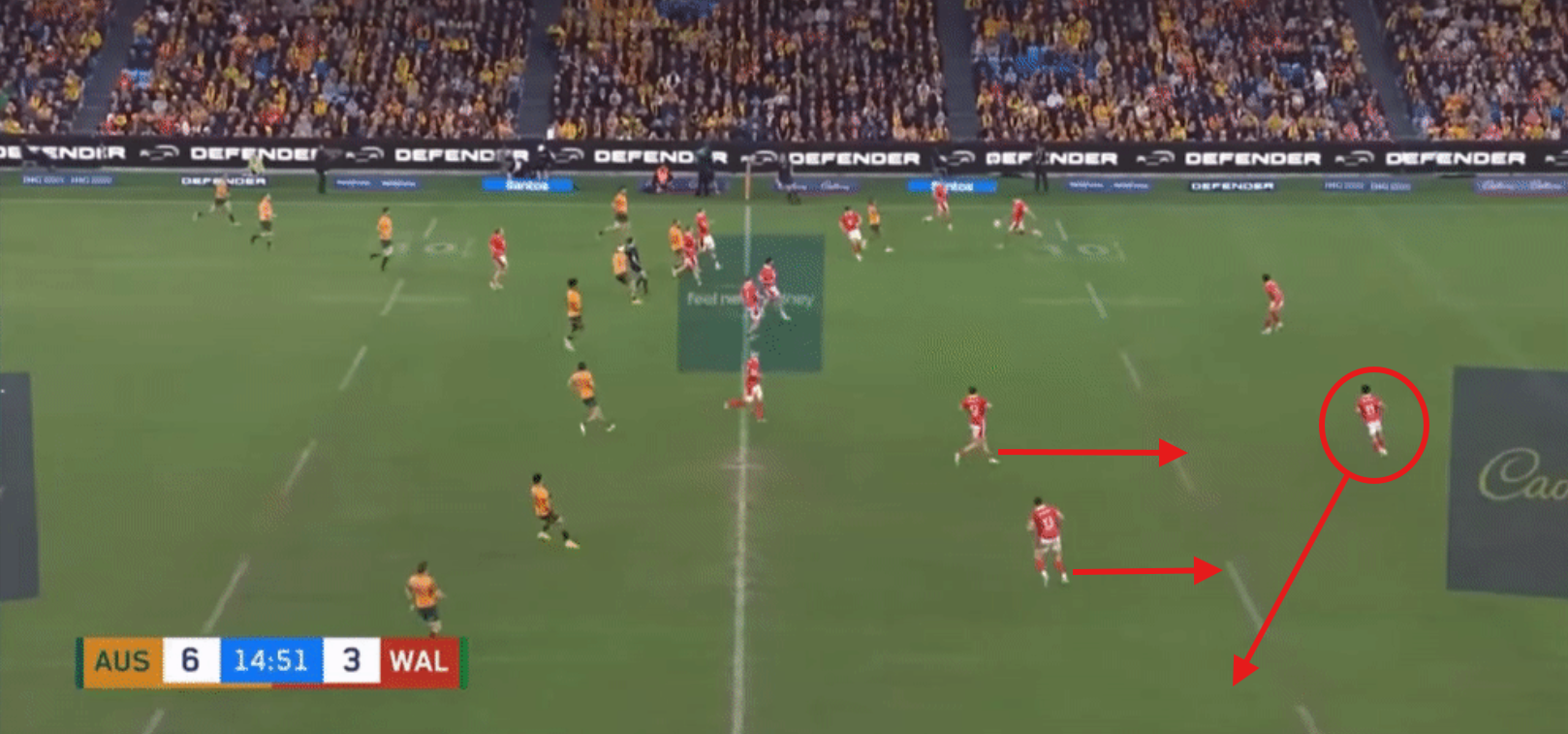

In the clip above Rio Dyer travels a considerable distance to narrow any possible counter attack, presumably to get close to Ben Thomas to chase any kick that could come from the ball being shifted inside, and in the process occupies the space that Mason Grady and Owen Watkin are attempting to form up in.

If Dyer holds his width, Grady and Watkin form up faster, and Williams moves the ball inside for Thomas to get on the outside of the chasing Rob Valentini, then Cymru suddenly have Thomas, Grady, Watkin and Dyer in a four-on-three with half the width of the pitch available to exploit.

That pre-determined kick, rather than looking to play into space, ultimately brings about the killer blow for Cymru in the first clip from the first test as, rather than forming up and looking to play into the space at the top of the screen, Josh Hathaway kicks possession back to the Wallabies and they return with interest to score a match-winning try.

Then the second and third clips underline the issue with narrowing the counter attack as neither ball crosses that mid-point of the halfway line into the far half of the pitch where the space is, as the men-in-red come too short and end up carrying into dead ends.

Of course there’s an inherent risk in playing too expansively and “running away” from support. However, if the counter attack forms up quickly enough and the opposition defence can at the very least be forced into drifting, if not scrambling, then it reduces the possibility of turnovers being conceded.

When Cymru did opt to counter attack with intent, and move the ball to width, it didn’t produce brilliant results but it showed that, at the very least, we can take the ball on halfway and finish up creating the basis for phase play attack 20 metres further up the pitch. As long as we don’t kick it away unnecessarily, of course.

There’s a similar story from recovery of spilled possessions for Cymru, where the intent to play becomes more of a focus as generally the team are in a better position to switch from defence to attack going from defensive phase play to unstructured play.

Presumably through the messaging and lack of focus on expression from the coaching staff, there’s very little natural intuition to look to move the ball through the hands and play into space, especially when the game does become unstructured and some of the outside backs are in a position to exploit the disarray and space that comes with that.

When the ball is recovered Mason Grady does well to gain some ground and get Cymru on the front foot, with Ellis Bevan in quickly to kick off the next phase, but it seems there is no other option available than kicking possession down the field.

As the picture opens up we see a two-man overlap at the top of the screen, with what looks like Liam Williams stood with arms out, querying why the men-in-red would not play into that space. Dewi Lake also appears to be pointing towards the right-hand-side of the pitch.

And this is not a criticism of individual players, because the number of instances of this automatic shift to playing risk-averse and frankly negative rugby on turnover ball points to it being a team ethos driven by the coaches, rather than a coincidence that players who are happy to express themselves playing for their clubs suddenly go fully within themselves at test level.

Another example of good quality, front-foot turnover ball secured by Evan Lloyd, but the lack of ambition to play a bit starts with nobody stepping in to move possession away from the breakdown in the immediate absence of the scrum-half.

Then by the time Sam Costelow does get the ball in his hands he is kicking possession downfield rather than exploiting the space shown at the bottom of the screen with Cam Winnett and Mason Grady enjoying plenty of green grass on that right wing.

It’s more frustration because, as with kick receptions, when Cymru do get it right we look dangerous. See below how Ellis Bevan gets the ball moving quickly, Rio Dyer is off his wing into midfield and the overlap is worked on the right wing for what could well have been a try.

The final stop of this tour of transitions is a relatively new one, with the goal line dropout essentially becoming a third set piece since its introduction.

We’ve seen Ireland run pre-called plays to great effect after receiving a goal line dropout, with the Wallabies under Joe Schmidt attempting something similar in the first test against Cymru. Yet for the men-in-red there was a depressing predictability around the primary ball carrier trucking possession up before the attack has a look at what it wants to do.

Invariably that decision involved either kicking the ball away or just taking one-off runners off 9.

There’s no issue with using Aaron Wainwright to carry the ball back initially as such, although there could be consideration given to asking a less mobile player to do it and keep Wainwright on his feet, but it doesn’t have much of an impact overall as Cymru are not set at all to attack with any intent on phase two.

Sam Costelow is not a realistic option for the pull-back pass, and Nick Tompkins has ended up out of the game on the inside shoulder of the forwards pod, rather than ready to link the play out wide. We don’t see exactly what space opportunities there are across the Wallabies defence, but the reason the dropout is almost a third set piece is that the receiving team can choose where to target.

Ultimately it’s a wasted opportunity for Warren Gatland’s side, and suggests that very little thought has gone into this from a coaching point-of-view, as again we simply truck the ball up on a goal line dropout return in the second test.

Once more the frustration around this comes from the fact that there was a glimpse of what Cymru can do when returning a goal line dropout when setting up properly on phase two and having the intent to move the ball to width.

It’s another example where there’s no major line break, but it shows that the baseline achievement of having the ambition to attack is to switch into phase play some 20 metres further up the field from where the ball was received, and be on the front foot with a bit of momentum.

Ultimately it’s an area of the game where full-on progression is not the priority in a squad evolution at the level Cymru have experienced during 2024, however it raises questions around the overall culture that Gatland & co are developing when it comes to over-coaching and restricting players, rather than allowing them to express themselves and putting structure around that.

With the youthful exuberance and raw talent of these breakthrough stars, allowing them to relax and enjoy their rugby will be key for their development, rather than drilling skill and enjoyment out of them in some overly disciplined approach that Gatland is well-known for.

Hopefully, as these players continue to catch the eye at club level where attacking rugby is largely encouraged, a change of approach will follow from the national team in order for natural flair and innovation to find it’s why into the red jersey of Cymru once again.